The Marlboro Man: Advertising as myth

How did one of the most successful advertising campaigns of all time reshape American culture? This case study is an exploration of how the Marlboro Man transformed a struggling women’s cigarette brand into a global empire.

Read on.

Marlboro: The Brand Before the Campaign

Before it became a symbol of masculinity and freedom, Marlboro was a cigarette for women.

The brand was introduced in the US by Philip Morris Company in 1924. Philip Morris (1835-1873) was a British tobacconist and cigarette importer based in London. “Marlboro” gets its name from the factory on Great Marlborough Street, London. They were first marketed as "America's luxury cigarette" and were mainly sold in hotels and resorts.

Around the 1930s, it was starting to be advertised and positioned as a mild, refined cigarette for women. Early ads featured elegant women smoking, often accompanied by the tagline, “Mild as May.” The filters were a key selling point, designed to make smoking “cleaner” and more appealing to female consumers — some even had red filters to accommodate for red lips. Early packaging had a delicate, feminine touch, evoking luxury and sophistication.

In 1952, Reader’s Digest published an article titled “Cancer by the Carton,” which linked cigarette smoking to lung cancer. Public concern grew, and sales of unfiltered cigarettes started to drop. The tobacco industry needed a solution — filtered cigarettes were the answer. But they carried a problematic perception. Unfiltered cigarettes were seen as strong, raw, and masculine, while filters were perceived as delicate, refined, and feminine. Men didn’t want to be seen smoking a filtered cigarette, let alone one specifically marketed for women. For Philip Morris Co., this was a critical challenge and tremendous opportunity — if they could make filtered cigarettes acceptable to men, they could capture the entire market. The company needed to completely reposition Marlboro.

The Architects of the Rebrand

Filtered cigarettes were the future, but they had to be made desirable to men. The challenge wasn’t just marketing a product; it was reshaping perception, rewriting cultural codes, and making filters masculine.

From 1954 to 1957, the critical period when the Marlboro rebrand took off, Joseph F. Cullman III was the president of the Philip Morris Company. He became CEO in 1957, holding the position until 1978, overseeing Philip Morris as it grew into one of the most dominant tobacco companies in the world.

Cullman was a brilliant strategist and businessman. Under his leadership, the company aggressively expanded its reach, positioning Philip Morris as an international powerhouse, despite the emerging public health crisis.

For the Marlboro rebrand, he turned to Leo Burnett, one of the most influential advertising minds of the 20th century, and worked closely with him to ensure the marketing strategy aligned with Philip Morris’s long-term vision.

With an early career in journalism, Burnett’s foray into advertising began in earnest in the 1910s working for Cadillac and advertising firms in Indianapolis and Chicago before founding his own agency, Leo Burnett Company, in 1935 in the middle of the Great Depression.

"Make it simple. Make it memorable. Make it inviting to look at. Make it fun to read."

While other agencies focused on hard-sell tactics, Burnett had a different philosophy. He understood that people don’t just buy products—they buy status, identity, and aspiration.

His approach was character-driven branding, a technique that would define some of the most successful campaigns of all time. Burnett didn’t just create ads—he created icons. Some of his most famous creations include Tony the Tiger for Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes, the Jolly Green Giant for Green Giant, and the Pillsbury Doughboy for Pillsbury. Each of these characters transcended the status of brand mascots and became symbols embedded in the minds of consumers.

Burnett believed in advertising that connected to the core emotions of consumers—ads that didn’t just inform, but captivated, inspired, and resonated on a deeper level.

The Many Men of Marlboro

Burnett’s challenge with Marlboro was monumental: how do you make a filtered cigarette—the ultimate symbol of sophisticated femininity—into the toughest cigarette in America?

Marlboro needed to be stripped of its past.

In the 1950s, America was shaped by war, economic expansion, and a rapidly changing cultural landscape. According to the 1950 Census, approximately 89.5% of the total U.S. population identified as white.

Nearly half of adult American men were military veterans. Millions had served in World War II (1939–1945) and another wave had fought in the Korean War (1950–1953). This created a generation of men shaped by discipline, duty, and survival, returning to a country that expected them to embrace suburban domesticity and corporate stability.

The post-war economic boom fueled corporate expansion. Millions of men left farms and blue-collar jobs for office careers, climbing the corporate ladder in large bureaucratic companies. These suburban white-collar workers were described as conformist and risk-averse, defined by suits, commutes, and a growing sense of disconnection from the physical, hands-on work of previous generations

In addition, millions of working-class men worked in steel mills, coal mines, auto plants, railroads, and farms, forming the backbone of industrial America. Many belonged to tight-knit, male-dominated workplace cultures, where toughness, endurance, and camaraderie defined their identity.

By 1954, Marlboro needed to sell filtered cigarettes to veterans, working-class, and white-collar men.

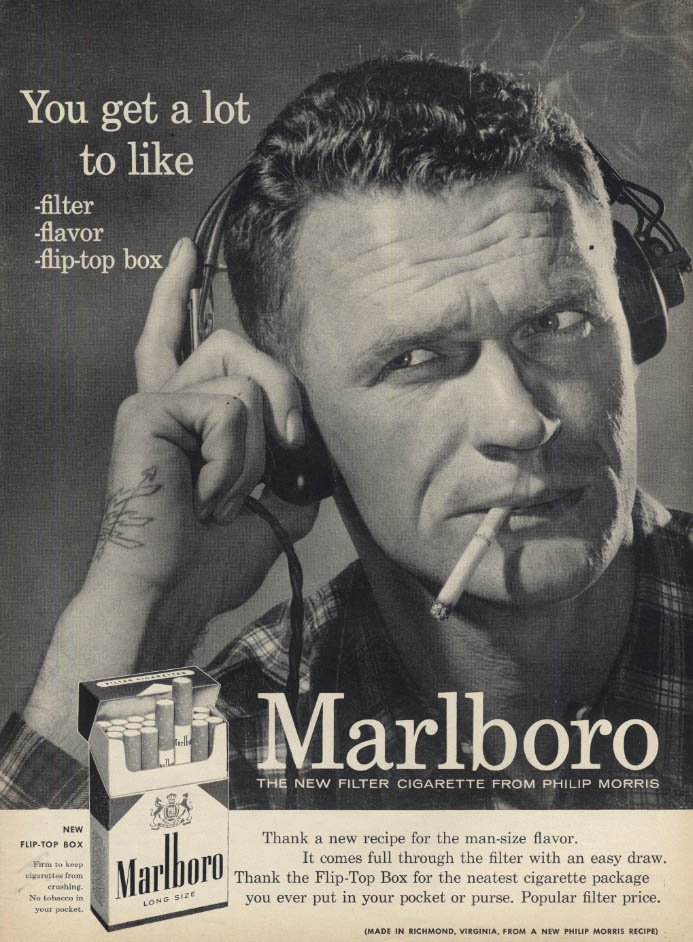

The first ads that came out in 1955 all featured veterans with their distinctive military hand tattoos. During World War I, servicemen began tattooing their military ID numbers—and later social security numbers—on their bodies for identification in case of injury or death. By World War II, tattooing had grown as a symbolic ritual among soldiers, marking their commitment, courage, and sense of camaraderie.

In 1955, one of the Marlboro Men stands out as a non-veteran.

Little did Burnett or Cullman know at the time, that this image would result in one of the greatest advertising campaigns of all time. In fact, it will take eight years for Marlboro to embrace the cowboy as the one and only Marlboro Man, leaving us with a single question.

What happened to the many men of Marlboro?

The Proto-Marlboro Man

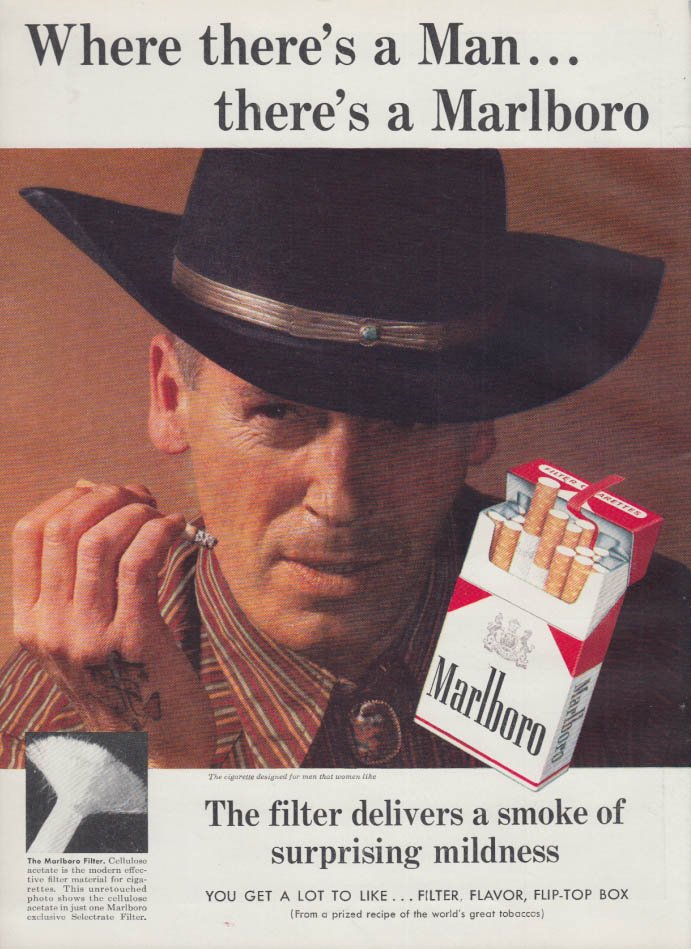

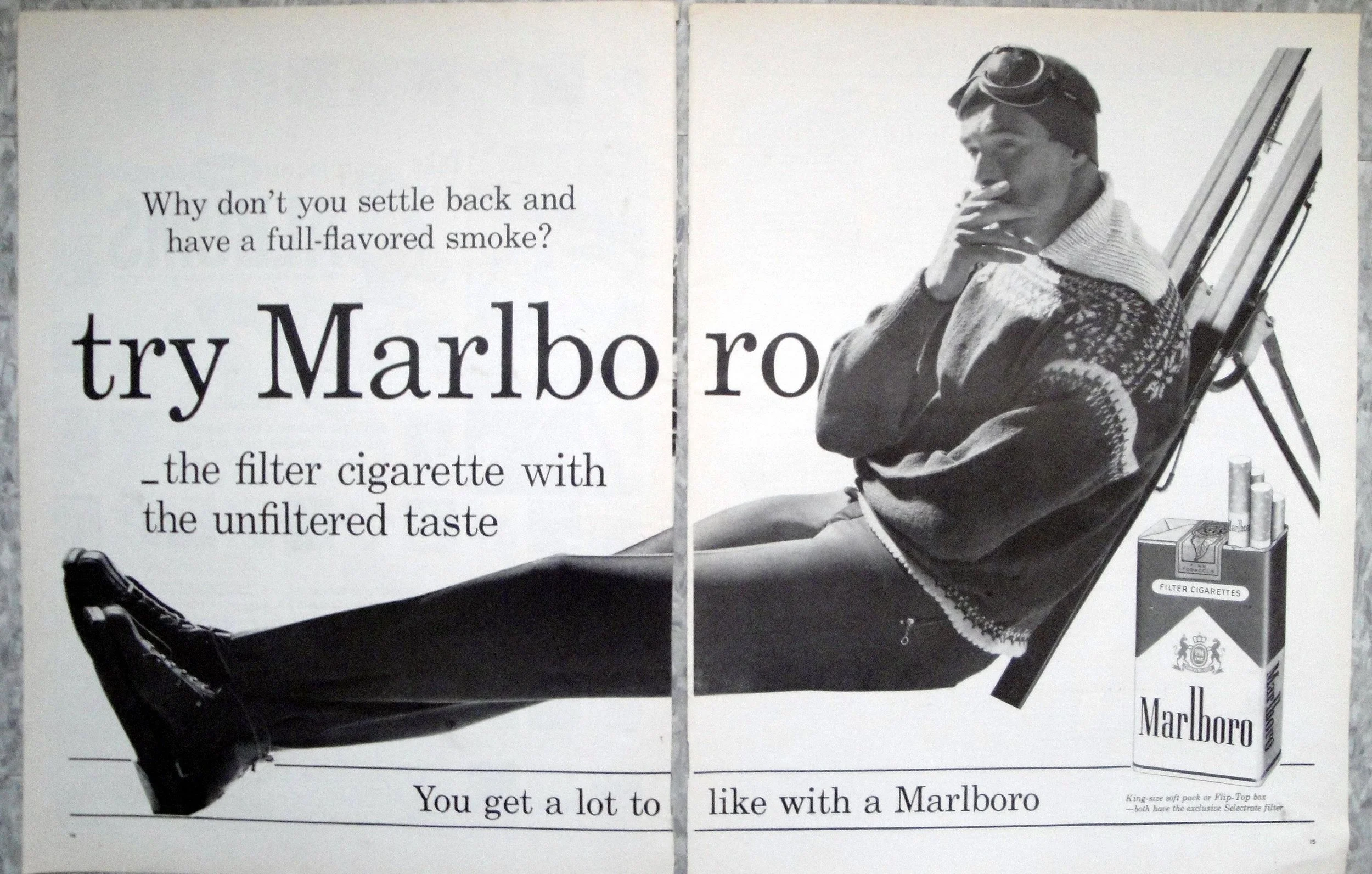

The men featured in the 1957 and 1957 Marlboro ad campaigns reflect a diverse portrayal of “mainstream” masculinity in post-war American society, showcasing a broad spectrum of "manly" identities — veterans, laborers, intellectuals, outdoorsmen, and the self-made men

These campaigns are a fascinating snapshot of post-war masculinity in America and reinforce different forms of masculine ideals of the 1950s.

Though masculinity is not one-size-fits-all, these men were united by the Marlboro cigarette.

But what of the cowboy?

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963: a Pivotal Year

In the 1950s, though the once vast frontier of the American West was becoming a relic of the past, cowboys were everywhere—on the big screen, in TV shows, in dime novels, and in the collective imagination of a nation that still saw the West as its ultimate myth of freedom and self-reliance.

John Wayne was one of the most prolific actors of the time and had established himself as Hollywood’s leading cowboy by the 1940s with movies like Stagecoach (1939, dir. John Ford) and Red River (1948, dir. Howard Hawks). His dominance continued into the 1950s with Rio Grande (1950, dir. John Ford) and Hondo (1953, dir. John Farrow). His deep voice, imposing presence, and no-nonsense approach to justice made him the quintessential American hero.

Still frame from Stagecoach (1939, dir. John Ford)

In 1954, there was no stronger, more aspirational, or culturally dominant figure than the cowboy. He embodied freedom, individuality, and rugged masculinity.

Still frames from Hondo (1953, dir. John Farrow)

By associating the Marlboro brand with this archetype, the campaign tapped into deep cultural currents and offered smokers a way to project their own masculinity and independence. The filtered cigarette, once dismissed as delicate and weak, became the toughest cigarette on the market.

By 1955, Marlboro's sales had surged to $5 billion—a remarkable 3,241% increase over 1954's figures, making it the best-selling cigarette brand in the world. The Marlboro Man became a cultural icon, symbolizing not just the brand but an entire generation’s ideals.

This laid the groundwork for the cowboy archetype that would later dominate. The cowboy symbolized all these characteristics in one figure, which explains why Marlboro eventually phased out this broader representation in favor of the Marlboro Country campaign.

It wasn’t just a cigarette anymore—it was a symbol of freedom, power, and untamed masculinity.

machine-fleur

Machine-Fleur (n.) In poetic and visionary language, a symbolic or mythic entity that merges the mechanical with the botanical.

How to be a flower?

Let beauty be your function.

How to be a machine?

Be devoted to function.

beauty

Beauty is the oldest form of technology. It is the softest, and yet the most powerful. It is not frivolous or decorative, but functional. It is a form of truth, that helps us remember who we are. Wherever there is beauty, there is coherence. And wherever there is coherence, there is power.

millennial existentialism

The unique angst and existential dilemma faced by Millenials — those born between 1981 and 1996.

It appears we are shaped by a convergence of societal, technological, and environmental changes, and face questions previous generations haven’t — but do we?

“Existentialism” is a philosophical movement that emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries, with thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus — though they themselves did not identify as “existentialists.”

It explores themes of individual freedom, choice, responsibility, and the search for meaning in a seemingly indifferent or absurd world.

While the word “Millennial” describes Generation Y who came of age in 2000 at the turn of the new millennium, “millennial” is an adjective that refers to a period of a thousand years, figuratively qualifying something that spans over a significant period of time.

So “millennial existentialism” could be:

— a perspective that delves into the fundamental questions of existence

— seeking to explore the endurance and continuity of these questions across epochs, regardless of time or place

— investigating how different generations grapple with and answer similar questions and challenges.

Millennial existentialism.

The relationship between a generation and the timeless, enduring questions that have persisted across time.

A poetic pursuit fueled by a relentless desire to discover a transcending principle and reveal our interconnectedness.

brand

To understand what a brand truly is, you have to go back to its roots. The word "brand" comes from the Old Norse brandr, meaning to burn. It began as a literal mark seared into wood, livestock, or metal, and was a sign of ownership, identity, and belonging.

Over time, it also came to mean "sword"—a tool of precision, forged in flame. A sword doesn’t waver—it stands for something. It slices through the noise, protects what matters most, and commands attention. It delivers its message with power.

In French, brand translates as “marque” or mark—a stamp of ownership, a declaration of identity, a symbol that speaks without words. Like a coat of arms or a flag, it is a bold declaration of our values and a rallying point that others recognize and follow. It says, “This is who I am. This is what I stand for.” It is the mark we leave on the world.

To create a brand is to take a stand. It’s to plant your flag and draw your sword. It is a way of being recognized without words.

During the Industrial Revolution, the concept of “brand” underwent a significant transformation. In a rapidly expanding marketplace filled with mass-produced goods, brands became essential for distinguishing products—soap, clothing, food—from their competitors. A brand was no longer just a physical mark; it became a symbol of quality and a badge of trust, signaling reliability and consistency to consumers navigating an increasingly crowded and impersonal economy.

This evolution laid the foundation for branding as we know it today: a promise that stands out in the noise.

If you are building, running, or marketing a brand — whether it’s a business brand or your own personal brand — how long does it take you to answer these questions:

What is the flame that fuels your purpose?

What is the sword that defines your stance?

What is the mark you want to leave on the world?

Because a brand isn’t just what you create—it’s who you are. And if it’s done right, it has the potential to last forever.

A personal brand is no different. Your name can carry the same weight. It can be a beacon for what you believe in, a banner that others rally behind.

To build a personal brand is to take ownership of your name—to imbue it with purpose and meaning. It’s not just about what you do, but what you stand for. A name that carries weight isn’t about chasing trends or fleeting recognition. It’s about crafting a legacy.

What does your name stand for?

How will it be remembered?

legacy

In an age that glorifies rapid launches, viral moments, and instant gratification, there’s a quiet rebellion in choosing a different path, a deliberate march toward something deeper, greater, and enduring. This philosophy is about crafting not for now but for the ages.

Building for Timelessness

When we think of the great cathedrals of Europe—those towering monuments to art, faith, and human ingenuity—we see a testament to patience and vision. Many of these cathedrals took centuries to complete. Generations of craftsmen worked on projects they knew they’d never see finished, driven by the belief that their work contributed to something eternal.

Deep Branding allows us to build not just for ourselves but for a legacy. The brands that stand the test of time are those that resist the pull of fleeting trends — they are timeless. They are built with intention, aligned with deep truths, and designed to resonate long after their creators are gone.

Redefining Speed

The world of business often prioritizes speed: launch quickly, iterate faster, grow exponentially. An obsession with speed can lead to shallow results and work that fails to connect. Brands that chase the latest trend become disposable.

True agility is about moving deliberately and creating with purpose. Each step considered and aligned with a larger vision. Each action, however small, a brick laid in the foundation of something greater.

The Slower I Get, the Faster I Move

In a world addicted to speed, focusing on legacy is revolutionary. It prioritizes quality over quantity, depth over superficiality, and meaning over metrics. It attracts audiences who value authenticity, care, and intention — turning customers into lifelong brand fanatics.

Brands that embrace this philosophy differentiate themselves from the crowd of disposable brands chasing short-term gains. They create for the future and build for the ages.

They become unforgettable.

mediocrity

We are living in a new era —

—one that is both disrupted and redefined by the force of social media. Where once cut-throat competition and scarcity ruled our thinking, we are now witnessing a profound shift—one that is making room for excellence, collaboration, and a new standard of possibility.

Social media is a disruptor — yes. But not just for businesses, influencers, or individuals. It is a disruptor of human potential. For the first time in history, we have a real-time broadcast of what humans can achieve: unparalleled health, unimaginable wealth, globe-spanning travel, jaw-dropping beauty, and lifestyles we didn’t dare dream of in the past. Success is no longer a story written in books—it is seen and shared on screens, accessible to anyone with a smartphone. These new possibilities break through what we once considered the limits of achievement.

Mediocrity, as a default, simply no longer works.

But there’s something more important happening alongside this visibility. Social media is also ending competition. That sounds counterintuitive, but look closer. Take what I witnessed just today: LACMA shared a post and a “competitor”—the Hammer Museum—showed up in the comments, not as a rival, but as a friend.

It was a moment that revealed a bigger truth: the age of isolation and hoarding attention is over. Institutions, businesses, and people can now amplify each other.

Success doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game—it’s something that grows when shared.

This collaborative spirit has the potential to build bridges in places we never imagined. When museums support one another on Instagram, patrons can flow between them, discovering new art, new experiences, and deepening their connection to culture. The same is true for creators, entrepreneurs, and even everyday individuals. Social media allows us to see that lifting others up doesn’t threaten our success; it enhances it.

The shift doesn’t stop there. Social media also holds us to a higher standard when it comes to peace and reconciliation. In war zones across the world, everyday people—“commoners” with nothing but a phone—broadcast their lives, their fears, their tragedies. This isn’t curated content; it’s raw and real.

It’s no longer possible to hide violence or sweep suffering under the rug. The world is watching.

This shared witness to war and destruction makes violence unacceptable in a way it hasn’t been before. Social media’s visibility has created a collective call for peace, for nonviolence, for solutions.

So here we stand, on the edge of a new paradigm. Social media is disrupting competition, mediocrity, and even the systems that perpetuate violence. In their place, it offers connection, collaboration, and a new vision of what’s possible.

Whether in art, business, or global justice, the future belongs to those who support, amplify, and build bridges. The era of competition is ending. What comes next is up to us.

ecstasy

La Gravure sur bois de Flammarion est une gravure sur bois anonyme, ainsi nommée car on retrouve pour la première fois sa trace dans le livre de Camille Flammarion publié en 1888, L'Atmosphère : météorologie populaire, au chapitre « La forme du ciel ». Elle est également appelée Gravure au pélerin en référence au personnage représenté.

Le trait est une rencontre.

Le pélerin voyageur intoxiqué,

à genoux s’est enivré d’une fleur.

La rose comme une flèche le traverse.

Transpercé au coeur,

tranché par le plan céleste,

pris d’un rapt d’extase,

il voit la machine superbe

et entend les anges.

Les fleurs ne sont-elles pas

Les étoiles de la terre?

ASTRUM*

Fleur inventée, imaginaire,

Suspendue dans ton huile précieuse.

Sécrétion secrète,

Voluptueuse,

Magique,

Qui ensorcelle et envoûte,

Comme une pluie d’étoiles et de baisers.

*Astrum est l’huile précieuse et magnifique créée par Reålea Skincare qui a inspirée cette page. Elle mélange magistralement jasmin égyptien, rose turque, bois de santal de Nouvelle-Calédonie, myrrhe somalienne, fleur d'hélichryse croate, fleur de champaca indienne, romarin, géranium égyptien, cèdre de l'Atlas marocain, huile d'ambre fossilisé de l'Himalaya et huile d'or.

L’Autre. Une fragrance. Un trait. Une rencontre, qui nous révèle à nous-même ces dimensions que l’on ne soupçonne pas.

Bridget Riley, Study for Kiss, (1961)

Le trait de l’olfaction.

La rose émet des molécules volatiles odorantes. À l'intérieur du nez, elles se lient aux récepteurs olfactifs. Lorsqu'une molécule odorante se lie à son récepteur correspondant, une cascade de signaux chimiques ouvre des canaux ioniques et génère un potentiel d'action. Les signaux sont envoyés au cerveau, qui les associe à des souvenirs et des émotions puis, après, les identifie.

Cupid Shooting Arrows at the World Globe

Attributed to Otto van Veen

Netherlandish, 1608 or shortly before

bliss

Bliss, B-Corps, & Reishi Cappuccinos

Yesterday, I felt so alone and here I am now, sitting at Erewhon alone again and I’m in bliss. Why is every sip of this “reishi cappuccino” so pleasurable? I think it’s because it is sweet. Profoundly sweet. Like a hug from my best friend. And that could make me cry right now. It’s 6:30 pm and I’m having a mystical experience. I feel like I’m out of my body, turning into a cloud, floating high, around myself. A profound sense of peace. Warm, euphoric. Like falling in love, but it’s just me. It’s just me and everything else. Everything else to be fallen in love with — sound, shape, movement.

It’s funny how everyone looks familiar when you feel like this. The girl in front of me is eating a raw carrot (with skin on), dipping it in a fresh raw omega-3 dairy and gluten-free no soy, no canola dip. California women are the hottest babes under the sun. This woman is beautiful. She’s opening a box of Simple Mills Almond Flour Rosemary & Sea Salt crackers. The box reads, “Feel what good food can do. Food has the power to transform how you feel. To help you live your fullest life.” Is that what’s happening to me?

The girl has a bite of Honey Mama’s Oregon Mint raw cacao. She’s glowing. There’s an olive tree behind her. I wonder what her name is. She’s on her phone. Watching her is so pleasurable. She radiates health. She nibbles on another bite of chocolate and pulls out a kombucha — GT’s Alive Ancient Mushroom Elixir.

Somehow, over the course of 14+ billions of years of evolution, this woman and I are sitting across from each other, both drinking ancient mushrooms. I drink the last sip of my faux-cappuccino from my disposable cup, gazing up at the outdoor heaters. It’s June and it’s cold in Venice. So we heat the outside. Is this right? Is this wrong? Should we have ever left Africa? What took us? Boredom? Folly? The call of the unknown. Maybe that’s what it is — the mystical, the unknown. Maybe life is more than survival? Maybe life is more than surviving? Maybe life is sitting under a heater outside in June in Venice, California. Maybe evolution is pleasure? Why not? Someone had to decide to put clothes on and go north. And here I am, with my empty cup under the warmth of the heater. Me, her, and this little bird eating her gluten-free crumbs.

I love Erewhon. The name comes from the word nowhere. It’s an establishment. LA iconic. The founders Michio and Aveline Kushi started selling macrobiotic and organic foods out of a 10’ x 20’ stall below street-level in Boston back in 1966. They moved to Los Angeles in 1968. Erewhon was the first store of its kind in America. It was built upon the core idea that “if we fill our bodies with the very best that Earth has to offer, we can become our best selves.”

Their paper bags read, “We are proud to be a Certified B-Corp, using business as a force for good.” This reminds me of Angelina Jolie’s post on Instagram about her Atelier Jolie x Chloé collaboration. “It was important to me to work with Chloé, one of the first luxury brands to be a B Corp.” Ange cares so whenever she shares, I care to listen.

I look around and realize I am surrounded with the hottest babes in LA. A total of seven women are sitting around the patio. It feels so good to be around women. No need to talk or make eye contact. Just being in each other’s presence. Women are the salt of the earth. Maybe this is another key ingredient to my blissful cup. The girl two tables down has a sweater that reads, “A little slice of heaven” on the back. Feels like a great title for whatever I’m writing — “Erewhon Venice: A Little Slice of Heaven.”

Indeed, I feel bliss. I haven’t moved an inch. I sincerely wonder what is causing it. The reishi mushrooom? The cacao? A deeply satisfying day of work? The shower I took this morning? My hair? Maybe it’s being 32? Or the last 4.54 billion years? From the Big Bang to the reishi cappuccino, to think this moment is the culmination of 13.8 billion years is dizzying. I am here, sitting under the heater, writing in my notebook ordered on amazon.com. I love Amazon. Imagine if it became a B Corp. Imagine if every time we buy something there, we regenerate a piece of the Amazon. I wonder if some of our land is forever lost. Maybe lost land lives elsewhere. Somewhere in stories and songs? Somewhere in me?

The B Corporation might be one of the greatest economic revolutions of the 21st century. “B Lab Certification is a third-party standard requiring companies to meet social, sustainability, and environmental performance standards.” Accountability and transparency. Angelina Jolie shared a link to Chloé’s official page explaining what it means to them. I love when brands have a manifesto. “Women Forward. For a fairer future.” “To bring positive impact to people and the planet. This is our purpose guiding all we do…” “Women as change agents.” You bet. “We are proud to be part of this community of leaders, driving a global movement of people doing business as a force for good.”

I wonder what’s next for us — Homo sapiens. Sustainable capitalism and reishi cappuccinos. I feel the warmth of the heater on my cheeks. This is millennial existentialism — fast lives in ancient bodies. Absurdly beautiful.

yosemite

AFTER 1851 — Upon visiting Yosemite Valley for the first time, I realized the impact of naming the land on the way we perceive the environment. The symbols created through language become a civilizational lens through which to see and read the landscape. El Capitán, Bridalveil Fall, Three Brothers, Sentinel Rock, Cathedral Rocks, Half Dome... were the names given by Lafayette Bunnell, a pioneer and member of the Mariposa Battalion — the first non-indigenous group to enter the valley.

BEFORE 1851 — Before Yosemite, the Miwok people called the valley Ahwahnee, meaning “large mouth,” a reference to the gaping mouth of a bear. El Capitán was called too-tok-ah-noo-lah, “measuring-worm stone” from the legend of the measuring worm that saved two children who were stranded when the rock grew. Bridalveil Fall was pohono, “huckleberry patch.” Sentinel Rock was loya, “long water basket.” Cathedral Rocks was poo-see-na-chuck-ka, “large acorn cache.”

NOW —

the name of the land

a reflection

a relationship

mountains

words are not your name

what is your name?

are you nameless?

speak the unspeakable

We are listening…

We hear something…

a silence that tells everything.

Names tell stories.

Silence speaks the truth.

“Dieu n’est atteint que dans la mesure où on l’a depouillé de tout ses noms.”

Yosemite Valley has a geological story, a natural story, an indigenous story, a colonial story, and a contemporary story — all unfolding at same time. There is an immense opportunity with AR (Augmented Reality) to create layers over the landscape to honor these many stories.

Originally published on 10/23/2023 environmentalism

As above, so below.

As within, so without.

Environmentalism begins and ends with our selves.

Environmentalism is realizing that separation is an illusion.

What is going on outside of ourselves

is a perfect, total, and complete reflection

of what is going on inside ourselves.

Being an environmentalist

is realizing the inter-connectedness

of our inner and outer lives.

And taking full responsibility.

As environmentalists, we know clearing the inside clears the outside.

As environmentalists, we know clearing the outside clears the inside.

So could the fear of clearing our outside,

simply reflect our fear to clear our inside?

Originally published on 9/21/22