The Marlboro Man: Advertising as myth

How did one of the most successful advertising campaigns of all time reshape American culture? This case study is an exploration of how the Marlboro Man transformed a struggling women’s cigarette brand into a global empire.

Read on.

Marlboro: The Brand Before the Campaign

Before it became a symbol of masculinity and freedom, Marlboro was a cigarette for women.

The brand was introduced in the US by Philip Morris Company in 1924. Philip Morris (1835-1873) was a British tobacconist and cigarette importer based in London. “Marlboro” gets its name from the factory on Great Marlborough Street, London. They were first marketed as "America's luxury cigarette" and were mainly sold in hotels and resorts.

Around the 1930s, it was starting to be advertised and positioned as a mild, refined cigarette for women. Early ads featured elegant women smoking, often accompanied by the tagline, “Mild as May.” The filters were a key selling point, designed to make smoking “cleaner” and more appealing to female consumers — some even had red filters to accommodate for red lips. Early packaging had a delicate, feminine touch, evoking luxury and sophistication.

In 1952, Reader’s Digest published an article titled “Cancer by the Carton,” which linked cigarette smoking to lung cancer. Public concern grew, and sales of unfiltered cigarettes started to drop. The tobacco industry needed a solution — filtered cigarettes were the answer. But they carried a problematic perception. Unfiltered cigarettes were seen as strong, raw, and masculine, while filters were perceived as delicate, refined, and feminine. Men didn’t want to be seen smoking a filtered cigarette, let alone one specifically marketed for women. For Philip Morris Co., this was a critical challenge and tremendous opportunity — if they could make filtered cigarettes acceptable to men, they could capture the entire market. The company needed to completely reposition Marlboro.

The Architects of the Rebrand

Filtered cigarettes were the future, but they had to be made desirable to men. The challenge wasn’t just marketing a product; it was reshaping perception, rewriting cultural codes, and making filters masculine.

From 1954 to 1957, the critical period when the Marlboro rebrand took off, Joseph F. Cullman III was the president of the Philip Morris Company. He became CEO in 1957, holding the position until 1978, overseeing Philip Morris as it grew into one of the most dominant tobacco companies in the world.

Cullman was a brilliant strategist and businessman. Under his leadership, the company aggressively expanded its reach, positioning Philip Morris as an international powerhouse, despite the emerging public health crisis.

For the Marlboro rebrand, he turned to Leo Burnett, one of the most influential advertising minds of the 20th century, and worked closely with him to ensure the marketing strategy aligned with Philip Morris’s long-term vision.

With an early career in journalism, Burnett’s foray into advertising began in earnest in the 1910s working for Cadillac and advertising firms in Indianapolis and Chicago before founding his own agency, Leo Burnett Company, in 1935 in the middle of the Great Depression.

"Make it simple. Make it memorable. Make it inviting to look at. Make it fun to read."

While other agencies focused on hard-sell tactics, Burnett had a different philosophy. He understood that people don’t just buy products—they buy status, identity, and aspiration.

His approach was character-driven branding, a technique that would define some of the most successful campaigns of all time. Burnett didn’t just create ads—he created icons. Some of his most famous creations include Tony the Tiger for Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes, the Jolly Green Giant for Green Giant, and the Pillsbury Doughboy for Pillsbury. Each of these characters transcended the status of brand mascots and became symbols embedded in the minds of consumers.

Burnett believed in advertising that connected to the core emotions of consumers—ads that didn’t just inform, but captivated, inspired, and resonated on a deeper level.

The Many Men of Marlboro

Burnett’s challenge with Marlboro was monumental: how do you make a filtered cigarette—the ultimate symbol of sophisticated femininity—into the toughest cigarette in America?

Marlboro needed to be stripped of its past.

In the 1950s, America was shaped by war, economic expansion, and a rapidly changing cultural landscape. According to the 1950 Census, approximately 89.5% of the total U.S. population identified as white.

Nearly half of adult American men were military veterans. Millions had served in World War II (1939–1945) and another wave had fought in the Korean War (1950–1953). This created a generation of men shaped by discipline, duty, and survival, returning to a country that expected them to embrace suburban domesticity and corporate stability.

The post-war economic boom fueled corporate expansion. Millions of men left farms and blue-collar jobs for office careers, climbing the corporate ladder in large bureaucratic companies. These suburban white-collar workers were described as conformist and risk-averse, defined by suits, commutes, and a growing sense of disconnection from the physical, hands-on work of previous generations

In addition, millions of working-class men worked in steel mills, coal mines, auto plants, railroads, and farms, forming the backbone of industrial America. Many belonged to tight-knit, male-dominated workplace cultures, where toughness, endurance, and camaraderie defined their identity.

By 1954, Marlboro needed to sell filtered cigarettes to veterans, working-class, and white-collar men.

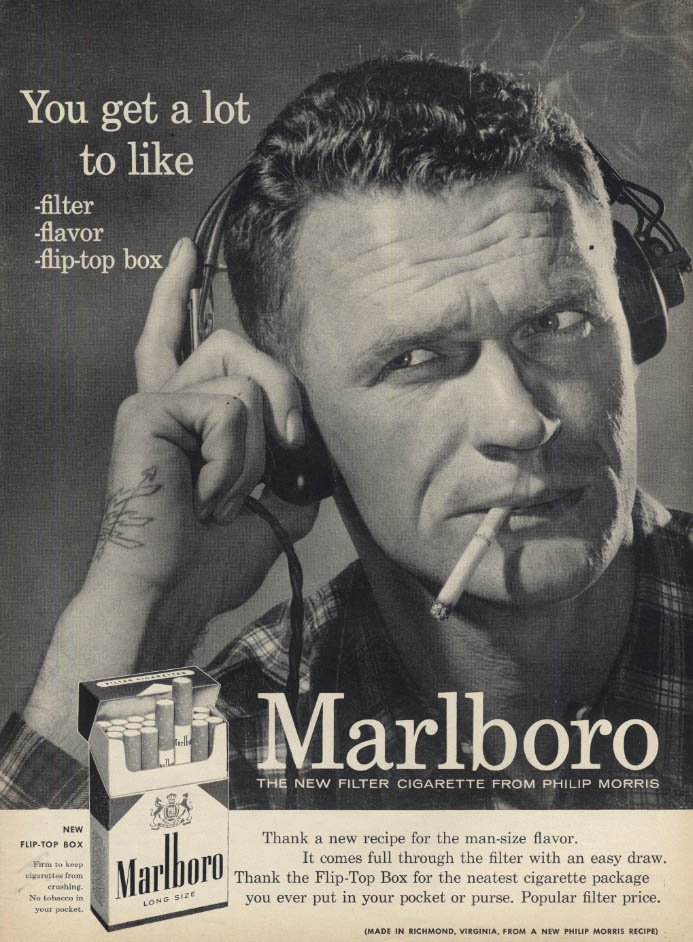

The first ads that came out in 1955 all featured veterans with their distinctive military hand tattoos. During World War I, servicemen began tattooing their military ID numbers—and later social security numbers—on their bodies for identification in case of injury or death. By World War II, tattooing had grown as a symbolic ritual among soldiers, marking their commitment, courage, and sense of camaraderie.

In 1955, one of the Marlboro Men stands out as a non-veteran.

Little did Burnett or Cullman know at the time, that this image would result in one of the greatest advertising campaigns of all time. In fact, it will take eight years for Marlboro to embrace the cowboy as the one and only Marlboro Man, leaving us with a single question.

What happened to the many men of Marlboro?

The Proto-Marlboro Man

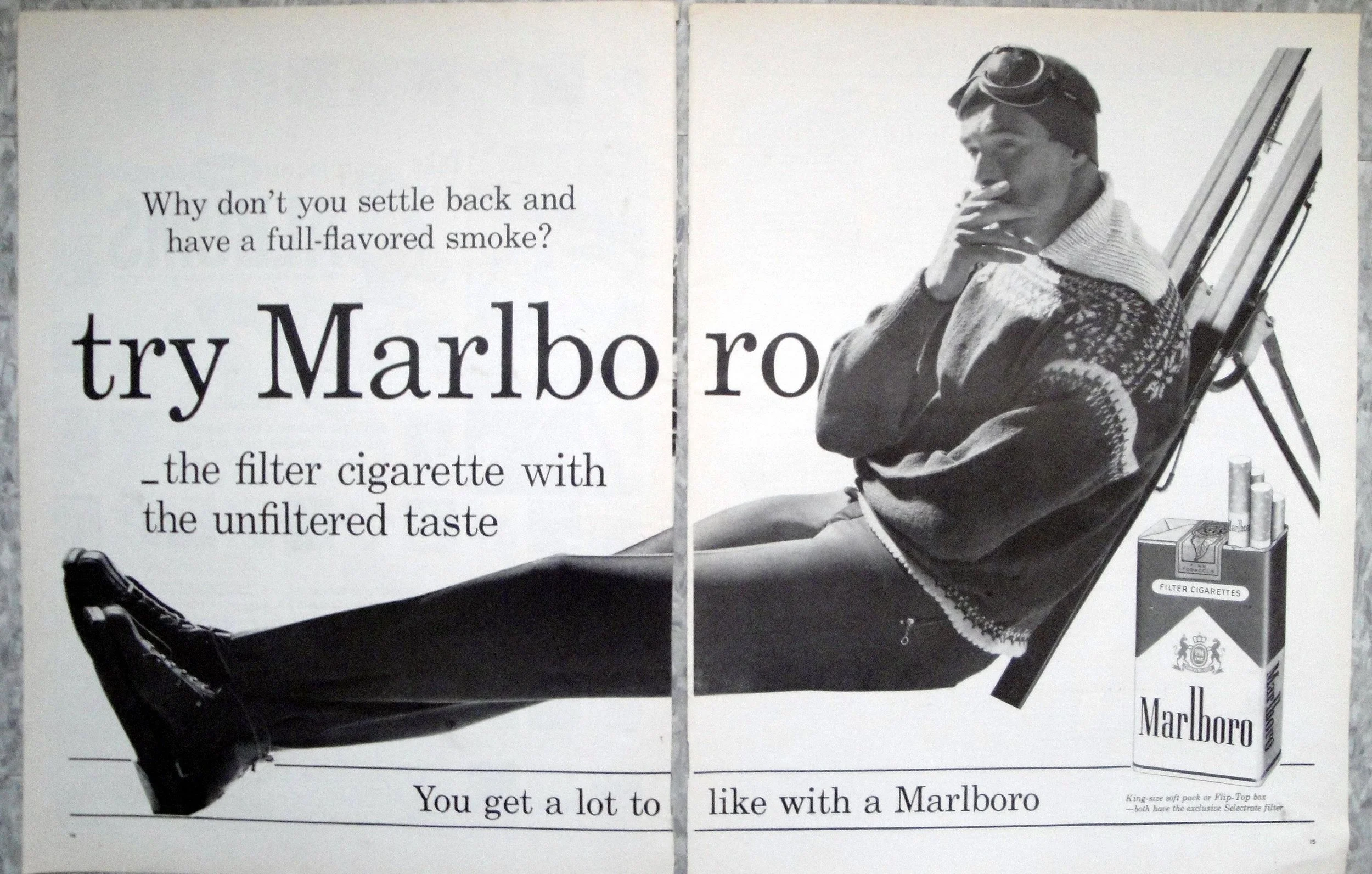

The men featured in the 1957 and 1957 Marlboro ad campaigns reflect a diverse portrayal of “mainstream” masculinity in post-war American society, showcasing a broad spectrum of "manly" identities — veterans, laborers, intellectuals, outdoorsmen, and the self-made men

These campaigns are a fascinating snapshot of post-war masculinity in America and reinforce different forms of masculine ideals of the 1950s.

Though masculinity is not one-size-fits-all, these men were united by the Marlboro cigarette.

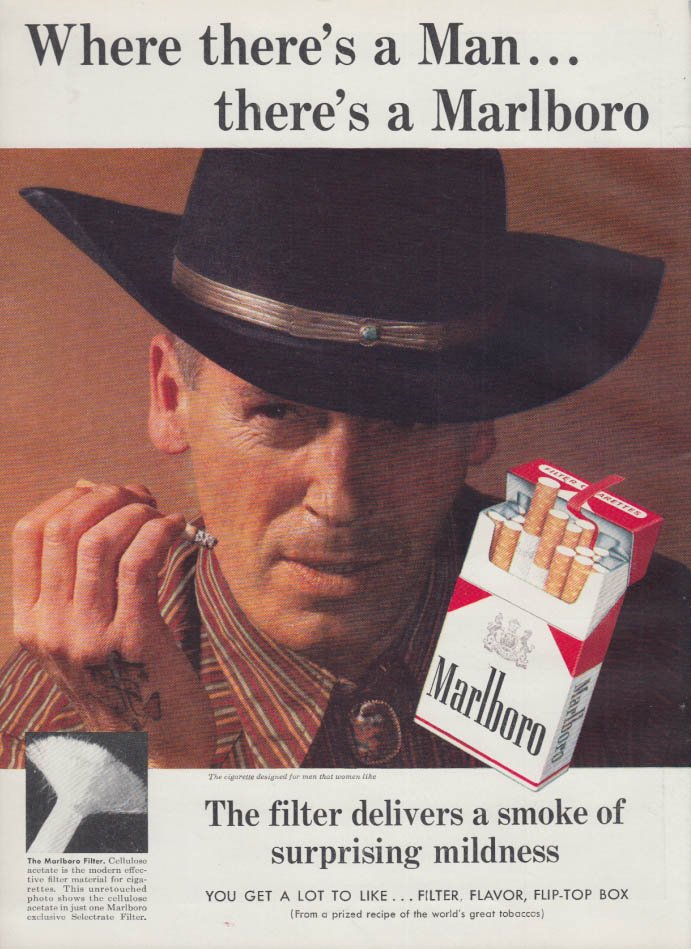

But what of the cowboy?

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963: a Pivotal Year

In the 1950s, though the once vast frontier of the American West was becoming a relic of the past, cowboys were everywhere—on the big screen, in TV shows, in dime novels, and in the collective imagination of a nation that still saw the West as its ultimate myth of freedom and self-reliance.

John Wayne was one of the most prolific actors of the time and had established himself as Hollywood’s leading cowboy by the 1940s with movies like Stagecoach (1939, dir. John Ford) and Red River (1948, dir. Howard Hawks). His dominance continued into the 1950s with Rio Grande (1950, dir. John Ford) and Hondo (1953, dir. John Farrow). His deep voice, imposing presence, and no-nonsense approach to justice made him the quintessential American hero.

Still frame from Stagecoach (1939, dir. John Ford)

In 1954, there was no stronger, more aspirational, or culturally dominant figure than the cowboy. He embodied freedom, individuality, and rugged masculinity.

Still frames from Hondo (1953, dir. John Farrow)

By associating the Marlboro brand with this archetype, the campaign tapped into deep cultural currents and offered smokers a way to project their own masculinity and independence. The filtered cigarette, once dismissed as delicate and weak, became the toughest cigarette on the market.

By 1955, Marlboro's sales had surged to $5 billion—a remarkable 3,241% increase over 1954's figures, making it the best-selling cigarette brand in the world. The Marlboro Man became a cultural icon, symbolizing not just the brand but an entire generation’s ideals.

This laid the groundwork for the cowboy archetype that would later dominate. The cowboy symbolized all these characteristics in one figure, which explains why Marlboro eventually phased out this broader representation in favor of the Marlboro Country campaign.

It wasn’t just a cigarette anymore—it was a symbol of freedom, power, and untamed masculinity.